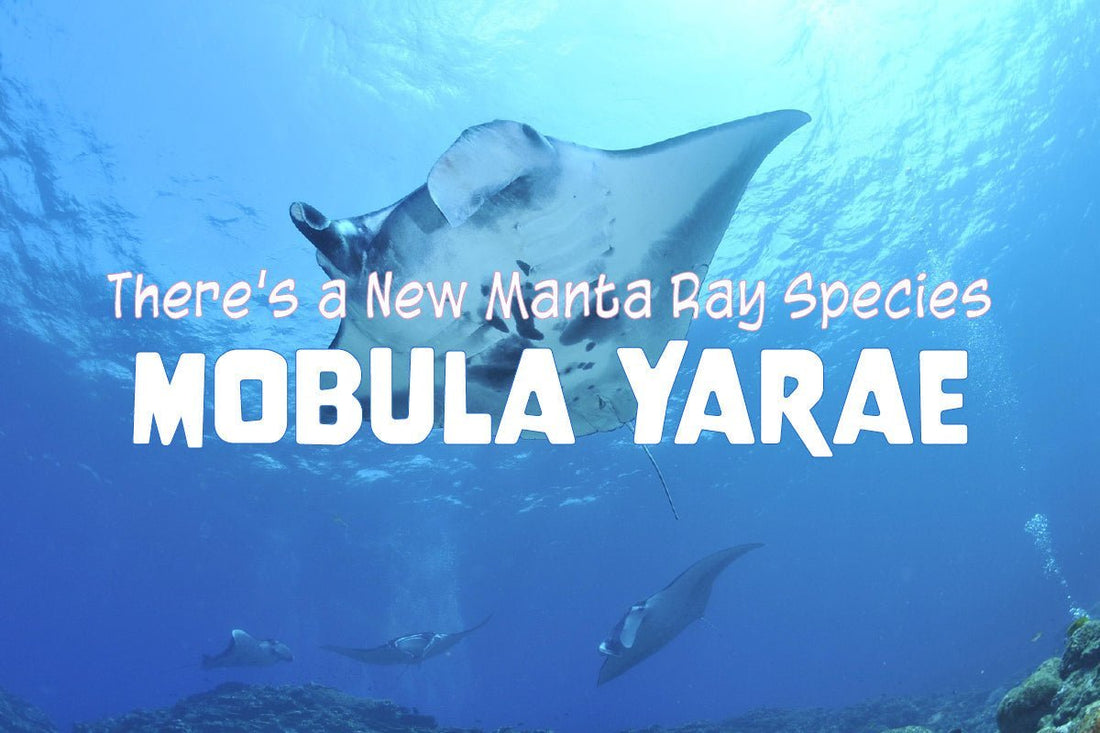

There’s a New Manta Ray Species: Mobula Yarae

Angela ZancanaroShare

For years, divers and marine scientists believed there were only two types of manta rays: the reef manta and the oceanic manta. But in 2024, a third species was formally described Mobula Yarae, a smaller manta found in the Atlantic Ocean off the coasts of Brazil, the Caribbean, and the Gulf of Mexico.

This discovery doesn’t just expand the manta family, it’s a reminder of how much we still have to learn about our oceans.

A Quick Backstory on the Discovery

The journey to Mobula yarae started in 2009, when Dr. Andrea Marshall (aka the “Queen of Mantas”) noticed something odd while diving off Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. The manta she encountered didn’t match the known reef or oceanic species. Over the next 15 years, researchers across Brazil, Mexico, and Florida documented hundreds of similar mantas and worked behind the scenes to collect genetic samples, spot pattern data, and ultimately, a type specimen that could confirm it as a new species.

The new manta was officially named Mobula yarae, named in honor of Brazilian goddess Iara (or Yara), the "lady of the waters." It’s the first new manta species to be described in over a decade and it's one of the largest new vertebrate species discoveries in recent history.

Meet the Mantas

All manta rays belong to the Mobula genus which is a group of large, cartilaginous rays that includes both the well-known giant mantas rays and their smaller, deep-diving cousins, the devil rays. Of the 11 recognized species in the Mobula genus, Mobula alfredi, Mobula birostris, and Mobula yarae are the largest and most iconic members of the Mobula family.

With wingspans reaching over 20 feet, they’re the largest rays in the world and they have the largest brain-to-body ratio of any cold-blooded fish. They show signs of intelligence, problem-solving, and even self-recognition in mirrors, something only a handful of animal species can do.

Mantas are filter feeders, gracefully swimming with their mouths open to collect plankton and tiny fish. A single manta can consume up to 13% of its body weight in food daily. But for all their size and strength, mantas are also slow to reproduce. The females give birth to just one pup every 2–5 years after a gestation period that can last over a year. This slow life cycle makes them especially vulnerable to threats like fishing, pollution, and habitat destruction.

How to Tell the Three Manta Species Apart

While all manta rays share the same elegant form and feeding style, each species has distinct traits that help scientists and divers identify them in the wild. Here’s how to tell them apart:

Mobula yarae – Atlantic Manta Ray

Wingspan: Estimated 3.5–4.5 meters (11–15 feet)

📍 Range: Coastal western Atlantic – Brazil, Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico

ID Features:

- Narrow dark Y- or anchor-shaped marking on the dorsal (top) side, just behind the head—distinct from other manta species

- Ventral (belly) spots tend to be smaller, more tightly clustered, and located farther back on the abdomen than those of reef or oceanic mantas

- May lack large smudgy shoulder patches seen in birostris or the bilaterally symmetrical spot rows of alfredi

- Pectoral fins may appear slightly shorter and more angular compared to other species

- Dorsal coloration is often a deeper, more uniform black with less shading contrast

Migration: Believed to be coastal and semi-resident, with movements similar to Mobula alfredi. Still under active study.

Mobula alfredi – Reef Manta Ray

Wingspan: Up to 5.5 meters (18 feet)

📍 Range: Indo-Pacific reefs – East Africa to Hawaii, including the Maldives, Indonesia, and northern Australia

ID Features:

- Dorsal marking behind the head often appears as a broad T- or Y-shaped dark pattern, but the edges are blurred, forming more of a V in black

- Ventral (belly) spots typically appear between the gill slits and along the trailing edge of the pectoral fins and abdominal region

- Spot patterns are often bilaterally symmetrical, with clusters of small spots across the central belly and near the gills

- Rounded wing tips and a stockier, triangular body shape

- Dorsal surface varies from gray to black, often with lighter shoulder patches or chevron shapes

- Tail is typically equal to or shorter than the disc width

- Gill plates are large with rounded terminal lobes; coloration is usually black but can occasionally appear all white

Migration: Semi-resident; known to return to the same cleaning stations and reefs over time, with some seasonal movement between regional reef habitats

Mobula birostris – Oceanic Manta Ray

Wingspan: Up to 7 meters (23 feet)

📍 Range: Worldwide in open ocean – tropical, subtropical, and some temperate waters

ID Features:

- Dorsal shoulder markings form two mirror-image, right-angled white triangles, creating a broad “T” shape in black on the back

- Minimal markings between the gill slits, often leaving the central area pale or unmarked

- Ventral (belly) spots are generally sparse, larger, and more irregular than reef mantas, often clustered near the rear of the abdomen

- Inside of mouth and cephalic fins usually shaded black, as is the trailing underside edge of the pectoral fins (except in rare leucistic morphs)

- Long, pointed wing tips and a sleeker, more aerodynamic body

- Dorsal coloration is typically dark overall, with low contrast and occasionally a pale trailing edge

- Tail may have a knob-like bulge where a vestigial spine is embedded at the base

- Gill plates are large, with fused lateral lobes and rounded terminal lobes, most often colored black, though fully white plates have been documented

Migration: Highly migratory; oceanic mantas travel across entire ocean basins and can be found in deep pelagic zones far from land. Some individuals are known to return to seamounts and offshore cleaning stations seasonally.

Why Does This Matter?

Understanding these differences isn’t just for scientists or ocean nerds. It matters because each manta species has different behavior, habitat needs, and threats. Reef mantas rely on specific reef systems and may be more affected by tourism and pollution. Oceanic mantas face risks from bycatch and shipping traffic. And now, Mobula yarae introduces an entirely new population that may need unique protections.

When all mantas were lumped together, conservation strategies often missed the mark. With three distinct species, we can now push for region-specific protections, better fishing regulations, and research funding that targets actual needs.

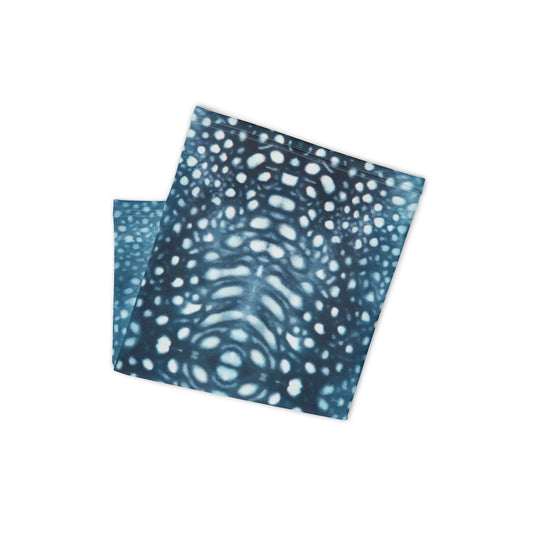

Submit Your Manta Photos

One of the most powerful tools in manta research is your camera. Every manta ray has a unique pattern of spots on its belly that stays the same throughout its life, just like a human fingerprint. By photographing these markings and sharing them with researchers, divers and snorkelers around the world are helping scientists track individual mantas across oceans and over time.

These images are used to:

- Identify individuals and build photo ID databases

- Track movements and migrations across regions or even countries

- Estimate population sizes and monitor local populations

- Understand behavior, site fidelity, and even social interactions

- Detect injuries or scarring, often caused by fishing gear or boats

And now, with the discovery of Mobula yarae, these contributions are more important than ever. This new species is still poorly documented, and photos from citizen scientists could help map its true range and behavior—data that’s essential for conservation.

You can help by:

- Taking clear, respectful photos of the underside of a manta when it swims overhead (never chase or touch a manta)

- Noting details like location (GPS if possible), time, date, water depth, and number of individuals

- Uploading your images to MantaMatcher.org – the global database for manta and mobula identification

Even if you’ve only seen a manta once, your photo might be the missing link in a migration story—or even the first documented sighting of Mobula yarae in a new location.

📸 Your snapshot could make waves in marine science. So next time you see a manta, aim for the belly, and become part of the discovery.

The Bigger Picture

The discovery of a third manta species proves one thing: we still have so much to learn about the ocean. Mantas aren’t just beautiful—they’re complex, intelligent, and vulnerable. And as divers, snorkelers, and ocean lovers, we get to be part of the story.